The Life and Games of Jeremy Blaustein

By John Szczepaniak

|

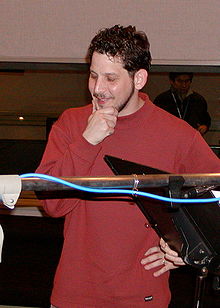

As a married father of three with a black belt in matsubayashi-ryu

karate, Jeremy Blaustein will happily speak about his love of Japan, his

many cats, and telling his son Pok?mon stories. He casts an unassuming

figure - just a regular guy looking after his family. Many people won't

realise the vast number of games he has worked on over the past 18

years. So many games in fact, that there is probably not a single person

reading this who has not either experienced one of them or knows

someone who has. While he hasn't yet reached Creative Director on a

project, Blaustein's work as a freelance localiser, translator, writer

and voice director has given him a unique opportunity to work alongside

some of the most prominent people on some of the best games in the

industry. He has had a hand in shaping for its western audience

everything from established franchises such as Metal Gear Solid, Silent

Hill and Castlevania, to lesser known cult-classics such as Shadow

Hearts, Sky Odyssey and Senko no Ronde. He was even involved with the

creation of Shenmue on the Dreamcast.

INDEX

PAGE 2 Born in New York, 1966, Blaustein went on to read Asian Studies at University. As he explained it, "I wanted to be able to communicate with a foreign culture of some type, something 'exotic' and Japanese was certainly that. I always had the sense that Asian countries may have figured out some of the deeper truths about reality than we had here in the West." Fresh out of university in 1991, Blaustein found himself in Chicago when Jaleco USA were hiring. He landed a job as Assistant Producer, though it was to be short-lived. "Oh, man, I was only there for like a couple of months before I got myself fired by getting angry." Prior to this, though, Blaustein was given a fascinating view into how the old guard of games developers operated. As he explained, "It's interesting because it's a snapshot of a certain kind of relationship during a certain period, that hasn't existed for a long time. It makes you realise what small potatoes videogames were back then, and how they were viewed. And we were dealing with tiny budgets, tiny amounts of money, tiny bits of memory. Tiny little games, you know? To look at the games we have now, and these huge launches, and these multi-million dollar things, it's hard to believe they're the same thing as Shatterhand on the NES, like we were doing back then, or Whomp 'Em. I remember this meeting with my first boss Howie Rubin, the sound guy on Q*Bert, and he was like, we'll make a pizza game and call it Delivery Boy! And we'd write up these half-assed little game plans, and send them to Japan asking 'can you make a game like this?' And they would maybe throw a little team at you. We'll give you a team of three guys and they can work up this little game. Games were so innocent back then."

Later on at Jaleco, it was a misunderstanding over an illegible Japanese letter regarding Bases Loaded which led to Blaustein getting into an argument with his Japanese superior, ending his time there. Feeling the need to improve his Japanese, Blaustein went to grad-school in Japan, culminating in a Masters degree in Japanese Anthropology. After this he enjoyed, as he puts it, a three-month stint of general slackery in Kyoto before teaching English as a foreign language. "I did that for about a year. It was one of those chain English-language schools in Japan. I was not asked to teach a second year. I spoke too much Japanese to the students, I think... But, during my time at Jaleco I'd gotten my twin brother, Michael, a job there. He later went on to Konami USA and, in 1993, returned the favour by getting me an interview with Konami Japan in Tokyo." "I got the job at Konami Japan when Super Famicom and Sega were burning everything up in the 16-bit world." Rather than work in Research and Development, something which he'd always wanted, the young Blaustein was posted in the international business department - a single foreigner in a company employing over a thousand Japanese people. Recalling the time, he spoke of the difficulty getting ideas noticed by those in positions of creativity. In spite of this though, being a native English speaker meant he was asked to write the text for several Konami games, including Rocket Knight Adventures, Sparkster, Animaniacs, Biker Mice From Mars and others. It also allowed him to get an understanding how Japanese developers viewed the west. "The minds at Konami Japan were thinking: there are some games that we make that are going to be just domestic, and there are some games that we're going to make for overseas, because they like violence and we like violence less. We like lots of deep, rich RPG stories, with Japanese mythology, and they won't buy that. So we need to start developing a sports series. I was there when Konami started talking about developing a soccer series, and we were so far behind EA and companies like that. My direct boss was very big on the idea of getting that going. Look where they are now, with the Winning Eleven series."

"When I was getting started I basically advertised any Japanese-to-English translation. So I did some patents, semi-conductors, electronics, I transcribed American express consumer complaints. I did all sorts of stuff." This was at a time when the CD medium was becoming mainstream, due to the popularity of Sony's PS1, and an early freelance games localisation effort by Blaustein was Konami's Vandal Hearts. "It's interesting for a few reasons, though I'm seldom asked about it. It was a rather early strategy RPG for the American market and a serious effort at doing a good localisation all by myself. I played it a lot so I'm confident that it was internally coherent." His next project was Castlevania Symphony of the Night, and I asked if there had been any controversy regarding the religious iconography in it. "Do you just mean the crosses? Castlevania always had that same issue. Yeah, there was definitely some concern on Konami's part and mine as well, though we didn't really talk about it."

A renaissance and period of change Prefer to be known for other games With so much focus given to Metal Gear Solid, a series which has inspired hundreds of articles and podcasts, and the game which Blaustein is best known for, there is a vast back-catalogue of work which has been overshadowed. I asked if there were any other games he'd rather be known for.

"I think it was released alongside a Final Fantasy, and you literally couldn't have timed the thing worse if you wanted to. So yeah, I wish fans could have seen that one. And it got good reviews - everyone said it was great, one magazine said it was the best RPG of the year or something. It was critically acclaimed. It was by a real dark horse Japanese company too, some company called Sacanoth did it. And I know those guys worked their brains off too. This represented so much, it had so much effort. That's the remarkable thing about games - the good ones, the creators put so much effort, so much of their hearts into it, and they're not recognised. The industry is so rife with irony, the whole situation." "Games creators can have a vision and then they come out with something that breaks the mould. It achieves some cult notoriety, it creates a bit of a phenomenon which is then pursued by the bean counters. And at that point it's no longer a work of joyful creation for the game creators, because they've got the bean counters telling them that their market survey people think they can sell a million units of a game that fits these categories. So they then force the creators to make a game, they whip them into working 15 hours a day or whatever, and they get this soulless simulacrum of a game. God, it makes me sick." His work on Shadow Hearts also generated hostility from the fans of Koudelka, the game's predecessor. "In Shadow Hearts I changed Urmnaf to Yuri, because he was meant to be Russian. And yet I had people write me like death threats because of that. Well, not really, but I know that fans were really, really angry about it. Because the original, Koudelka, was like one of these cult hits."

Blaustein mostly recalls being dissatisfied with the names, something he wasn't allowed to change. "I remember being unhappy about a lot of these names. I was so unhappy about these. I struggled with all those names. I mean, in Japanese you have 'Appuru' for example. Now is that 'Apple' or is it 'Appulu'? You tell me! Also, the developers would tend to put in a name like Victor or Edward or Ted, and to me that sounds SO mundane. So I would make it 'Viktor' for example. But that still left me somewhat dissatisfied. I was trying to satisfy the demands of keeping it close to the Japanese, but still interesting enough." The game featured the deaths of several key characters, which created quite a strong emotional resonance in Blaustein. "As far as the deaths of the characters, I just rewatched the death of Nanami. That was pretty good stuff! Great music. Nice smooth dialogue. Many translators were on this project and they were divided up by character instead of just doing chunks of text. This was to maintain consistency of voice. No one but me was thinking about stuff like that in those days." Many agree, finding the portrayals to be heartfelt. By the time the final credits roll, describing each character's life after the in-game war ends, most players should admit to being quite choked up. "Isn't that great? And when you consider Suikoden, graphically it was quite cartoonish, and yet that doesn't prevent you from experiencing the emotion of the game. Because you knew those cartoons were representative of characters, and they didn't need to look like your next-door neighbour to feel they were human. It's a suspension of disbelief, and it's as if for games today the idea of engaging people to use their own imaginations is a bad thing - it's a bad word."

"I loved Valkyrie Profile. I am a huge fan of Norse mythology from way back. Some of it was frustrating (such as Frey being a girl, so I changed the name to Freya). I sure was disappointed that I wasn't asked to work on the Valkyrie Profile follow-up for PS2. I think the original Valkyrie attracted some good reviews at the time. Enough to make people desire a sequel. I had a lot of input into that one and enjoyed working on it." "Silent Hill 2 was a game intended from the start for the USA, because it had more blood and everyone was becoming hypersensitive about violence and gore in Japan." The other big series Blaustein is known for working on is Konami's Silent Hill, parts 2, 3 and The Room. The second holds a particularly special place in his heart, since he came aboard as a creative consultant for the team, not only dealing with the English text and directing the voice actors, but helping to formulate early story ideas.

"Forget about having started the game, even while Owaku was throwing around ideas for his story, they called me in to have a big conference and meeting about what I thought would be acceptable themes in America. There was a solid team of about four or five guys, including Owaku and the monster creator guy, Tsuboyama." With Blaustein having such a direct influence on the game, I thought it time to clear up a few questions which fans of the series have been asking over the years. Two long-running debates held by fans, such as those on igotaletter.com, pertains to the nature of Angela's past, and also what is being said during the 'voice whisper' which can occasionally be heard while playing. Blaustein stated categorically that the abuse Angela is speculated to have endured at the hands of her father, did indeed occur as part of Silent Hill 2's back story. He explained, "This is an easy issue to clear up. From the very earliest conversations that I was in on (the pre-script writing meeting), the team had the intention of including incest and sexual abuse in one of the character's backgrounds. They wanted, remember, to get at the very heart, or maybe I should say edges, of psychological pain. So we all knew precisely what we wanted with Angela in terms of her dialogue on paper and as performed. As you can see, it is also well reflected in her appearance. We thought about it all the time, in every scene. Just watch the scenes again. She gets physically ill when she thinks about her experience. It seems clearly depicted if you know what you are looking for." "As for the whisper, I am pretty sure it is just a little loop of one of the actors doing what we called at the time 'butsu-butsu' or 'hitori-goto' (mumbling or talking to himself) in the recording booth. I think they just snipped a loop and added some reverb. The Japanese sound guys would NOT have known what he was saying either, if I am right, because it was just unscripted adlib." "I would say it was without a doubt the single biggest influence I've had on a game. I don't think there was any other game where I was ever asked to have that much of an affect on the story. It was also unique in that series that I did all the translation myself, and I did all the direction myself - the voice direction and motion capture directing. It was completely unprecedented." Blaustein went on the share his personal reflections on the game, especially the emotional impact of the letter James Sunderland writes, and revealed an interesting anecdote from the recording booth. "I was reading through a SH2 FAQ and came across 'the letter' from SH2. I really loved it and wanted more readers to have a chance to see it. The scene where Maria reads it, if you have never seen it, is one of the three most emotional moments I have ever had with the actors. The actress cried after she read it and many of us were getting a little misty-eyed. Try to listen to it on Youtube if you can. It was a great moment."

|